Background

There is a long history of human settlement along The Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (RSGA) coasts, which have served as a focal point for economic development, transportation and trade, and the extraction of natural resources from the ocean below. Today, the RSGA ‘s coastal regions serve as a focal point for population growth, economic expansion, and diversity. As heavy industrial and fishing sectors decrease, the new potential to diversify the local and national economies are emerging in coastal locations, from aquaculture and wind farms to tourism and recreational activities. According to a recent assessment, an estimated 70% of RSGA’s coastline is significantly threatened by human activity, both directly and indirectly (Psomiadis, 2022, p. 61). Thus, there is an urgent need for an integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) program that focuses on the loss of natural habitats, the loss of biodiversity and cultural diversity, and the reduction in water quality.

The Meaning of ICZM and its Key Stakeholders in the RSGA Area

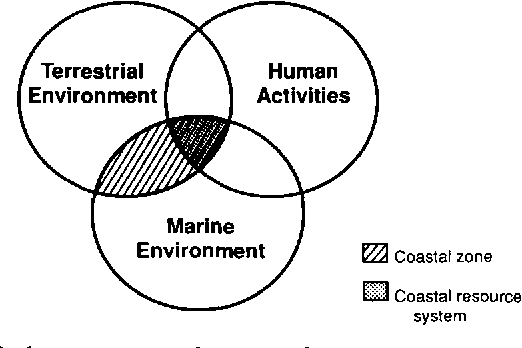

Numerous studies show that coastal and nearshore marine resources have a critical role in the long-term diversification of the local economy and the long-term sustainability of the region’s economy (Prosperi et al., 2019, p. 316). Commercial and residential development compete for limited space along the coast, which is why it is a magnet for coastal development. Coastal development is under increasing pressure as people move from rural areas to coastal cities. The coastal and marine ecosystem’s growth is threatened by uncontrolled, unplanned, and unregulated urban development. City-building policies must be closely coordinated and integrated with those for coastal and marine resource management to prevent causing irreparable harm to natural systems. The ICZM involves elements such as the terrestrial environment, human activities, and marine environment, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Implementing ICZM in coastal zone management is a fluid, ever-evolving process that serves various purposes. In the broadest sense, data collection and planning, decision-making; administration; and implementation monitoring are all part of this process. ICZM works with all stakeholders to examine the social goals in each coastal area and take action to achieve these objectives through informed involvement and cooperation. Environmental, economic, social, cultural, and recreational goals must all be balanced over the long term via ICZM (Al Ameri et al., 2022, p. 67). An integral part of ICZM is the integration of goals and the numerous instruments required to achieve those goals, which is referred to as “integrated.” Integrating all relevant policy areas, sectors, and administrative levels is what this term denotes. Therefore, ICZM must integrate the target territory’s land and marine components into its process.

The key stakeholders of ICZM in RSGA include the coastal or ocean users, Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs), landowners, businesses situated in or near coastal areas, Universities, research institutions, and users of the coastal and upland resources. Fishing, tourism and recreation, aquaculture, military, shipping and port operations, mining, subsistence activities, and offshore oil operations involve the coastal or ocean users’ stakeholders (Prosperi et al., 2019, p. 319). These groups must express coastal ocean space and resource demands and concerns. In addition, the coastal or ocean-based use ensures that coastal ocean space and resources are properly managed. Secondly, women groups, religious organisations, environmental NGOs on the local and international level, and youth organisations are some of the most important stakeholders in the coastal community. They work with residents to determine their most pressing priorities and needs and put on educational programs for the coastal community (Koutsi, and Stratigea, 2021, p.5). In addition, an NGO is accountable for providing government agencies with feedback, monitoring, and managing resources.

Another important stakeholder of ICZM is landowners, who ensure that land and unique habitats are well-maintained. According to Koutsi and Stratigea (2021, p.11), landowners in coastal areas are encouraged to protect themselves from erosion, flooding, and other natural calamities. Companies in or near coastal areas provide a significant portion of the construction, infrastructure, and equipment funding. They oversee putting money into the economy so that people can get jobs. Business owners in coastal areas also contribute to coastal management through taxes. Universities and research institutions engage the public in outreach activities and provide statistics and information to make informed policy decisions (Tetzlaff, 2021). At all levels, they provide programs for students with specific needs. In addition, research institutions act as spokespersons for sane, scientifically-based management of ocean and coastal resources. Finally, users of coastal and upland resources, such as farmers, foresters, loggers, and miners, employ environmentally friendly soil management and water allocation strategies that are long-term and sustainable.

PERSGA Organisation, its Key Roles, and Maritime Activities

PERSGA, part of the Arab League, has grown into one of the region’s main marine conservation groups. PERSGA is an intergovernmental entity that is dedicated to the preservation of the coastal and marine habitats in the region. Its member states are Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia’s Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen (Al Ameri et al., 2022, p. 71). Article XVI of the 1982 Jeddah Convention establishes PERSGA as an independent regional organisation for conserving the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden environment, with its permanent headquarters in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, as its legal base (Tetzlaff, 2021). The foundation of PERSGA was not officially revealed until the signing of the Cairo Declaration in Egypt in September 1995, during the First Council Meeting.

In 1997, PERSGA’s Strategic Action Plan was created, which provided a functional breakdown of the organisation’s various conservation initiatives and programs. PERSGA developed SAP under the presumption that it would be implemented in phases, with each phase having its own unique set of goals and areas of attention, following a step-by-step methodology (Mestanza-Ramón, 2019, p.9). Between 1999 and 2005, the Global Environment Fund (GEF) provided funding for the first phase of the SAP. Since 2006, PERSGA’s activity has been conducted by SAP Phase 2, which primarily emphasises the expansion and improvement of institutions throughout the long term.

PERSGA’s goal is to restore the Red Sea’s ecological balance and promote the long-term economic viability of the region’s coastal and marine resources. However, the goal of PERSGA is to carry out Ministerial Council’s Action Plan (Mestanza-Ramón, 2019, p.16). The RSGA’s coastal and marine resources must be managed and used sustainably. Reduced environmental risks, improved livelihoods for coastal people involved, and enhanced institutional, legal, and financial arrangements are all hallmarks of long-term sustainable management and use (Al Ameri et al., 2022, p. 81). PERSGA also aspires to maintain the current high quality of our common marine environment. PERSGA ensures that its use of the marine environment is sustainable and that new developments have minimum environmental implications as our region grows.

PERSGA’s role is to execute the Jeddah Convention, the Action Plan, and related Protocols, including specific plans for species, habitats, and related activities. Through the Jeddah Convention, the seven-member states of the Regional Seas Governance Area (RSGA) region recognise the necessity of integrating and coordinating their activities regarding their common marine and coastal resources (Gajdzik et al., p.3). Jeddah Convention takes a regional approach to conservation and management because the region’s health and its parts cannot be guaranteed without it. In addition, PERSGA’s primary goals are to protect the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden from pollution and to manage their resources efficiently. PERSGA’s program components support specialised and broad multipurpose programming.

The Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Marine Resources Stewardship Group is a policy-making body tasked with conserving the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden’s marine resources. It is also in charge of keeping tabs on the health of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden’s delicate marine ecosystems and identifying and coordinating regional conservation activities. PERSGA’s focal point gives regional information on the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden’s status and current challenges (Tetzlaff, 2021). In the process of helping regional and local environmental professionals, PERSGA offers regional and local training in many environmental areas. It is also a coordinating agency for environmental initiatives between PERSGA’s countries of origin and destination. In terms of its marine activities, PERSGA engages in the protection of marine areas, drafting marine letters, controlling marine pollution, building capacity, monitoring, and mitigating climate change.

The Main Maritime Rules, Regulations, and Policies Used by ICZM

ICZM is subject to a wide range of environmental and socio-economic effects, many of which go beyond the jurisdiction of local, regional, and even national governments. Various laws, regulations, and policies regulate this process, including and not limited to action plans, environmental conservation, equitable sharing of benefits, incorporation into local body plans, and engaging in legislation. In addition, ICZM should actively participate in the conflict resolution process while using spatial planning options (Kandrot, Hayes, and Holloway, 2021, pp. 4-7). Finally, ICZM should employ various tools to meet its coastal management goals.

The Main Challenges that ICZM Will Need to Deal with in RSGA Area in the Next 20 Years

Unplanned growth, a decrease in conventional and environmentally friendly sectors, coastal erosion, and a lack of good communications and transportation networks are just some issues that ICZM will have to address. Wasted investments, loss of long-term employment possibilities, and environmental and social degradation will result if the RSGA area is developed without proper planning (Villa, and Rašić, 2021, p.225). Due to unchecked growth in the tourist and other industries, this will happen in the next 20 years. The natural carrying capacity of coastal zones will be rapidly overburdened, resulting in pollution and degradation of natural resources, destruction of landscapes, and a decrease in the standard of living for local populations. Aside from destroying natural resources, such as tourist attractions and fish nurseries, this development will also harm the economy (Sanganyado, and Liu, 2022, p.107). This challenge exacerbates economic growth in the RSGA region.

A decrease in conventional and environmentally-friendly sectors in RSGA will cause unemployment, widespread emigration, and societal instability. Social and economic issues will arise when conventional sources of income like coastal fishing become unprofitable. As a result of these issues, more sectors may become unsustainable. Coastal erosion may damage natural habitats and human settlements, ruin economic operations, and imperil human lives. Therefore, climate-related Sea level rise will exacerbate erosion (Gajdzik et al., 2021, p. 11). In this case, accessibility is difficult for many coastal zones, especially islands. In the next 20 years, ICZM in RSGA should address the lack of good communications and transport networks, increasing marginalisation from the rest of Asia.

Reference List

Al Ameri, H.M., Al Harthi, S., Al Kiyumi, A., Al Sariri, T.S., Al-Zaidan, A.S.Y., Antonopoulou, M., Broderick, A.C., Chatting, M., Das, H.S., Hesni, M.A. and Mancini, A., 2022. Biology and conservation of marine turtles in the northwestern Indian Ocean: a review. Endangered Species Research, 48, pp.67-86.

Gajdzik, L., DeCarlo, T.M., Aylagas, E., Coker, D.J., Green, A.L., Majoris, J.E., Saderne, V.F., Carvalho, S. and Berumen, M.L., 2021. A portfolio of climate‐tailored approaches to advance the design of marine protected areas in the Red Sea. Global change biology, 27(17), pp.1-13.

Kandrot, S., Hayes, S. and Holloway, P., 2021. Applications of Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles (UAV) Technology to Support Integrated Coastal Zone Management and the UN Sustainable Development Goals at the Coast. Estuaries and Coasts, pp.1-20. Web.

Koutsi, D. and Stratigea, A., 2021. Sustainable and Resilient Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) in Remote Mediterranean Islands: A Methodological Framework. Heritage, 4(4), pp.1-28.

Mestanza-Ramón, C., Capa, M.S., Saavedra, H.F., and Paredes, J.R., 2019. Integrated coastal zone management in continental Ecuador and Galapagos Islands: Challenges and opportunities in a changing tourism and economic context. Sustainability, 11(22), (pp. 1-17).

Prosperi, P., Kirwan, J., Maye, D., Bartolini, F., Vergamini, D. and Brunori, G., 2019. Adaptation strategies of small-scale fisheries within changing market and regulatory conditions in the EU. Marine Policy, 100, pp.316-323.

Psomiadis, E., 2022. Long and Short-Term Coastal Changes Assessment Using Earth Observation Data and GIS Analysis: The Case of Sperchios River Delta. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 11(1), p.61.

Sanganyado, E. and Liu, W., 2022. Cetacean health: global environmental threats. In Life Below Water (pp. 107-120).

Tetzlaff, K., 2021. Regional seas programs and ocean acidification. Research Handbook on Ocean Acidification Law and Policy (pp. 94-122).

Villa, K.D. and Rašić, I., 2021. Integrating Coastal Zone Management into National Development Policies: The Case of Croatia. In Governing Territorial Development in the Western Balkans (pp. 221-238).